The reason why some may reject both the Westcott-Hort Greek text and the Textus Receptus (TR).

While both the Westcott-Hort Greek text and the Textus Receptus (TR) have been influential in the history of Bible translation, they have also been subject to criticism.

Westcott-Hort Greek Text

Emphasis on Alexandrian Text-Type: Westcott and Hort prioritized the Alexandrian text-type, represented by manuscripts like Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, over the majority text-type. Critics argue that this preference was subjective and led to the neglect of valuable textual evidence.

Questionable Methodology: Some scholars criticize Westcott and Hort's methodology, particularly their reliance on internal evidence and genealogical relationships between manuscripts. They argue that this approach was flawed and led to inaccurate conclusions.

Alleged Liberal Theological Bias: Some critics claim that Westcott and Hort's theological views influenced their textual choices. They argue that the Alexandrian text-type, which they favored, aligns more closely with liberal theological interpretations.

Textus Receptus (TR)

Limited Manuscript Base: The TR was based on a limited number of late Byzantine manuscripts. This limited base raises concerns about the accuracy and reliability of the text.

Scribal Errors and Corruptions: Due to the process of manuscript copying over centuries, the TR is susceptible to scribal errors and corruptions that may have accumulated over time.

Lack of Critical Apparatus: The TR lacks a critical apparatus, which would have provided information about variant readings and textual uncertainties. This makes it difficult to assess the reliability of the text.

It's important to note that modern Bible translations, such as the English Standard Version (ESV) and the New International Version (NIV), are based on more extensive textual evidence and scholarly analysis than either the Westcott-Hort text or the TR. These translations have benefited from advancements in textual criticism and a wider range of manuscript evidence.

Some readers may prefer to use a translation that reflects the latest scholarly findings. Recent scholarly findings in Bible translation continue to shape our understanding of the biblical text. Here are some of the key areas of ongoing research and discovery:

Textual Criticism:

• New Manuscript Discoveries: While major discoveries have slowed, ongoing research and analysis of existing manuscripts continue to refine our understanding of the original text.

• Digital Tools and Technologies: Advanced digital tools are revolutionizing textual criticism, allowing for more precise analysis of manuscripts and their variations.

Language Studies:

• Semantic and Syntactic Analysis: Deeper analysis of the original languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek) continues to shed light on the nuances of meaning and grammar.

• Cultural and Historical Context: Research into the cultural, historical, and social contexts of the biblical world helps to illuminate the meaning of the text.

Translation Philosophy and Methodology:

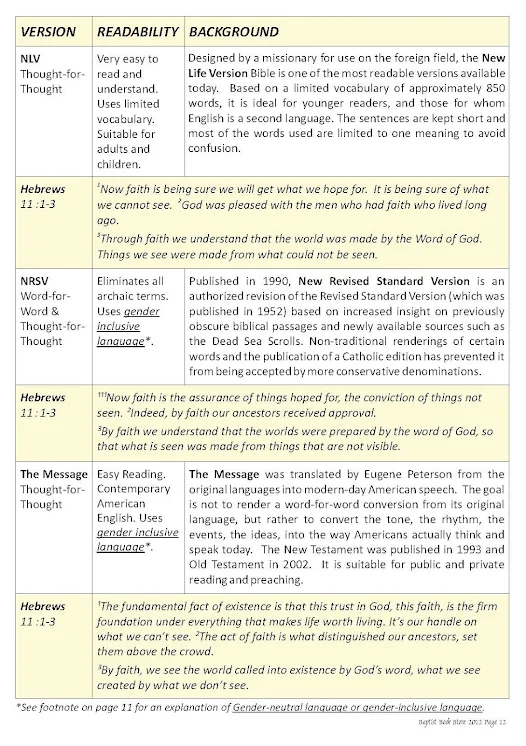

• Balancing Accuracy and Readability: Translators continue to grapple with the tension between literal accuracy and dynamic equivalence, seeking to produce translations that are both faithful to the original text and accessible to modern readers.

• Inclusive Language: Many translations are incorporating more inclusive language to reflect contemporary sensibilities and avoid gender-specific language that may not accurately represent the original text.

Interdisciplinary Approaches:

• Archaeology and Biblical Studies: Archaeological discoveries continue to provide valuable insights into the biblical world, helping to contextualize the biblical narrative.

• Literary and Historical Criticism: These disciplines offer new perspectives on the literary and historical aspects of the Bible, leading to fresh interpretations of the text.

It's important to note that while there are ongoing advancements in Bible translation, the core message of the Bible remains unchanged. These scholarly findings primarily help us to better understand the historical and cultural context of the biblical text, which can enrich our interpretation and application of its teachings.

We hope that the finest translation may be obtained by referring to all the manuscripts and early Bible translations:

Fact: We have over 5,800 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, making it one of the most well-attested ancient texts.

Here are some New Testament manuscripts and early translations:

Greek New Testament Manuscripts (Grouped by Century)

2nd Century (100–199 AD)

• Papyrus Manuscripts: Earliest and often fragmentary manuscripts, mostly on papyrus.

o 𝔓52 (Papyrus 52): Earliest known fragment, part of John (18:31–33, 37–38), dating to around 125–150 AD.

o 𝔓66: Nearly complete Gospel of John, dating to about 150–200 AD.

o 𝔓46: Contains most of the Pauline Epistles, dating to around 175–225 AD.

o 𝔓75: Contains large portions of Luke and John, dated to around 175–225 AD.

3rd Century (200–299 AD)

• Papyrus Manuscripts:

o 𝔓45: Portions of all four Gospels and Acts, dated around 250 AD.

o 𝔓47: Contains part of Revelation, dated to the 3rd century.

o 𝔓72: Contains 1 and 2 Peter and Jude, dated to the 3rd or 4th century.

4th Century (300–399 AD)

• Uncial Codices: Large manuscripts, mainly on parchment, written in uncial script.

o Codex Sinaiticus (ℵ or 01): Nearly complete Bible, including the New Testament, dated around 330–360 AD.

o Codex Vaticanus (B or 03): Nearly complete New Testament, dated to the 4th century.

o Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (C or 04): A palimpsest with portions of the New Testament, dated to the 4th or 5th century.

5th Century (400–499 AD)

• Uncial Codices:

o Codex Alexandrinus (A or 02): Nearly complete New Testament, dated to the 5th century.

o Codex Bezae (D or 05): Contains Gospels and Acts in Greek and Latin, dated to the 5th century.

o Codex Washingtonianus (W or 032): Contains the Gospels, dated to the late 4th or early 5th century.

6th Century (500–599 AD)

• Uncial Codices:

o Codex Claromontanus (D or 06): Contains Pauline Epistles in Greek and Latin, dated to the 6th century.

o Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus (N or 022): Purple-dyed manuscript with the Gospels, dated to the 6th century.

7th to 10th Centuries (600–999 AD)

• Uncial Codices: Fewer uncials are produced; minuscule writing becomes more popular.

o Codex Basilensis (E or 07), Codex Laudianus (E or 08), Codex Sangallensis (Δ or 037).

9th to 15th Centuries (Minuscule Period)

• Minuscule Manuscripts: Written in cursive, many thousands of these exist.

o Examples: Minuscule 1 (10th century), Minuscule 33 (9th century, "Queen of the Cursives").

Lectionaries (From 8th Century Onward)

• Lectionaries: Arranged by liturgical use, passages for specific days, from the 8th century onward.

o Examples: ℓ32 (10th century), ℓ185 (12th century).

________________________________________

Early Translations of the New Testament (Grouped by Century)

2nd Century

• Old Latin (Vetus Latina): The earliest Latin translations, from around the late 2nd century.

• Syriac Translations:

o Old Syriac (Diatessaron): Likely a harmony of the four Gospels by Tatian, around 170 AD.

o Peshitta: Standard Syriac version, emerging in the 2nd century and finalized later.

3rd Century

• Coptic Translations: In Egypt, there were several Coptic dialects:

o Sahidic: Southern Egyptian dialect, one of the earliest Coptic translations.

o Bohairic: Northern Egyptian dialect, translation completed later but based on early texts.

4th Century

• Gothic Translation: Made by Bishop Ulfilas, the Gothic Bible (4th century) represents the earliest translation into a Germanic language.

• Armenian Translation: Began in the early 5th century but initiated by missionaries in the 4th century.

5th Century

• Latin Vulgate: St. Jerome’s Latin translation, completed around 405 AD, became the standard in the Western Church.

• Georgian Translation: Created in the early 5th century, derived from Greek and Armenian sources.

• Ethiopic (Ge'ez) Translation: Created in the 5th or 6th century, based on both Greek and Syriac texts.

6th Century

• Old Church Slavonic: Developed by Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century for Slavic-speaking peoples but based on manuscripts that possibly had roots in the 6th century.

Translating the Bible from various manuscripts and early translations is a meticulous process that involves several steps to ensure accuracy and faithfulness to the original texts. Here’s a broad overview of how this is done:

1. Gathering Manuscripts

Scholars collect as many available manuscripts as possible, ranging from early papyrus fragments to later medieval codices. These manuscripts include significant texts from the Byzantine, Alexandrian, and Western traditions, among others.

2. Textual Criticism

Textual critics analyze these manuscripts to identify variations and determine which readings are most likely original. This involves comparing the texts and considering factors such as the age of the manuscript, the geographical distribution of the readings, and the quality of the scribes.

3. Creating a Critical Text

Based on textual criticism, scholars compile a critical text of the New Testament. This text represents the most accurate reconstruction of the original writings based on the evidence from various manuscripts.

4. Translation Committee

A diverse committee of scholars, fluent in the original languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek), is assembled. This team includes experts in linguistics, theology, and biblical studies to ensure a balanced and comprehensive translation.

5. Translation Philosophy

The committee decides on a translation philosophy—word-for-word (formal equivalence) or thought-for-thought (dynamic equivalence). Word-for-word translations (like the NASB) aim for literal accuracy, while thought-for-thought translations (like the NLT) aim for readability and capturing the intended meaning.

6. Drafting and Revising

Translators draft the initial version, often working in small teams. They cross-reference early translations like the Septuagint, Vulgate, and Syriac Peshitta, as well as consulting commentaries and linguistic studies. Multiple drafts are reviewed and revised to ensure clarity, accuracy, and faithfulness to the text.

7. Review and Feedback

The draft undergoes extensive review, both internally within the translation committee and externally by other scholars and language experts. Feedback is incorporated to refine and improve the translation.

8. Finalizing the Text

Once the translation committee agrees on the final version, it is proofread and typeset. The final text is prepared for publication, including any necessary footnotes, cross-references, and study aids.

9. Continuous Updates

Even after publication, translations are periodically reviewed and updated to reflect new manuscript discoveries and advances in linguistic understanding. This ensures that the translation remains accurate and relevant.

By following these steps, translators can produce a Bible that faithfully represents the original texts while being accessible and meaningful for contemporary readers. This process honors the integrity and depth of the Scriptures, ensuring that their transformative message continues to reach people across generations. It’s a remarkable journey of scholarship and faith.

There haven't been any major breakthroughs or groundbreaking discoveries in Bible translation in 2024.

Organizations like Wycliffe Bible Translators continue to work tirelessly to translate the Bible into languages spoken by millions of people around the world.

While there may not be a single "latest Bible translation finding" in 2024, the collective efforts of scholars and translators are gradually improving our understanding of the biblical text and making it accessible to more people worldwide.

To stay updated on the latest developments in Bible translation, you may want to follow organizations like Wycliffe Bible Translators or consult with biblical scholars.

It's important to note that Bible translation is a complex and ongoing process.

These are the reasons why we reject Verbal Plenary Preservation:

The doctrine of Verbal Plenary Preservation (VPP) asserts that God supernaturally preserved the original autographs of the Bible and that these original writings have been perfectly transmitted through subsequent copies to the present day.

While many Christians hold to this belief, there are several reasons why some reject VPP:

Lack of Explicit Biblical Support: Critics argue that the Bible does not explicitly teach the doctrine of VPP. While it affirms the inspiration and authority of Scripture, it does not explicitly claim that every word of the original autographs has been perfectly preserved.

Textual Criticism: Modern textual criticism, which involves the study of ancient manuscripts, demonstrates that the transmission of biblical texts was not error-free. Scribal errors, intentional alterations, and accidental omissions occurred throughout the copying process.

Historical and Cultural Context: The biblical texts were written in ancient languages and cultures, and their meaning can be influenced by various factors, including historical, cultural, and linguistic contexts. This can lead to differing interpretations and translations.

Different Textual Traditions: Different textual traditions, such as the Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Western, have emerged over time, reflecting variations in the transmission of the biblical text. These variations highlight the complexities of textual transmission.

Theological Implications: Some argue that VPP can lead to a rigid and inflexible approach to Scripture interpretation, hindering critical thinking and open dialogue.

It's important to note that while VPP is a common belief among some Christians, it is not a universally accepted doctrine. Many Christians hold to a more nuanced view of biblical authority, recognizing the complexities of textual transmission and the importance of careful interpretation.

Stay current with the latest manuscript discoveries and advancements in textual criticism. These resources can provide a more accurate and comprehensive foundation for translation.

Reject VPP and kick it's false teachers.